Allensworth

The Only California Town Founded and Financed by Blacks

At a time in history when blacks were being lynched on a weekly basis, and the U.S. Supreme Court essentially legalized racism in the form of Jim Crow segregation, blacks headed west in a desperate quest to achieve an idealized notion of American freedom. Dusty frontier towns were transitioning from being Mexican territories to part of the new Union State of California by September of 1850. California joined the Union as a free state, and this attracted blacks who were navigating life post-slavery. One of those blacks, an escaped slave who became the highest-ranking black officer in the Union Army, was Colonel Allen Allensworth. He led four other black men in founding the first and only town in California that was fully funded, designed, built, governed, and populated exclusively by black people.

While life at the turn of the twentieth century was hard for blacks due to forces outside their community, disparity also existed within. This was highlighted most prominently in the ongoing debate between W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, two great leaders of that period. While both men strongly advocated for black social and economic progress, they made a public show of their sharp disagreement on the process by which these measures were to be accomplished.¹ Directly in the midst of this civil rights quandary and heightened racial discrimination, five ambitious black men looked to California for a solution. Leading the way was Colonel Allensworth.

On April 7, 1842, Allensworth was born in Louisville, KY, the son of slaves named Phyllis and Levi. He was the youngest of thirteen children, all of whom were sold off to various Southern plantations. In the 1914 book The Battles and Victories of Allen Allensworth, the author, Charles Alexander — relying on a primary source — writes:

“His mother was the slave of Mrs. A. P. Starbird of Louisville, and as soon as Allen was old enough to be of any service, he was given to Mrs. Starbird’s son, Thomas, to be his little ‘nigger,’ as was the prevailing custom among such people at that time.”

It became apparent quite early that Allensworth was not going to abide a life of slavery. At around the age of 12, he was sold downriver to Mississippi for trying to learn how to read and write by playing school with young Thomas, and twice he attempted unsuccessful escapes. A third attempt, when the Civil War was already raging, resulted in Allensworth finding freedom at last. The war seemed to beckon Allensworth, who offered his service to the 44th Illinois volunteer Infantry as a civilian nursing aide. But the post did not satisfy his desire to help the war effort. To that end, he joined the Union Navy on April 3, 1863, becoming a first-class seaman at a salary of $18 per month. His pay quickly increased to $30 thereafter, and he served on various gunboats, including the Queen City, the Pittsburg, and the Cincinnati.

Allensworth started out as a clerk and the captain’s steward, but rose to the rank of first-class petty officer. After completing his service at the end of the war, he was honorably discharged on April 4, 1865, eleven days prior to the assassination of President Lincoln. Allensworth had the privilege of reuniting with his mother in Louisville briefly following the war, then he traveled to Mound City, Illinois to secure work. The Mound City Naval Yard hired him as a commissary, or clerk, to the commandant, and that lasted till 1867, when he decided to pool savings with his brother William and go into business for himself. That resulted in two restaurants located in different parts of St. Louis, which met with success from the start. After receiving an attractive offer from a prospective buyer, the brothers sold the establishments and Allensworth left his brother back in St. Louis while he moved on to new pastures.

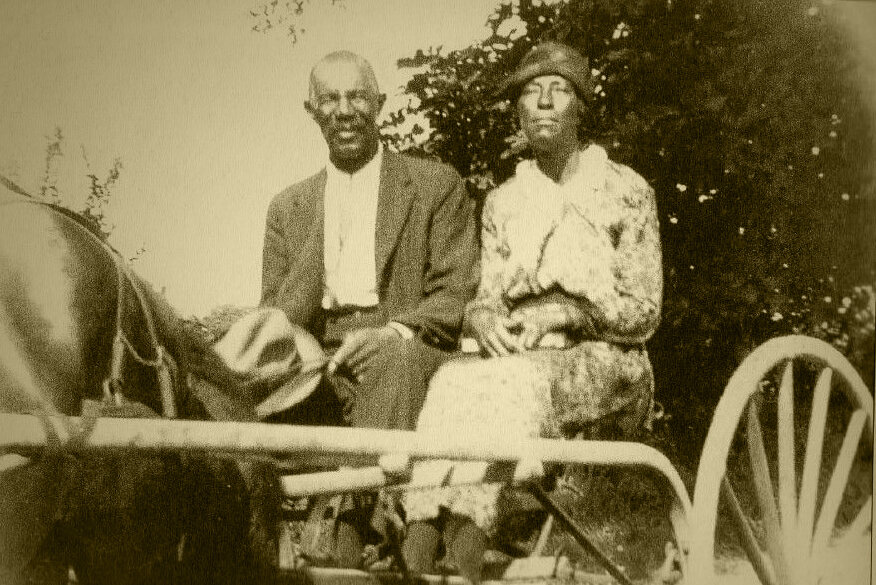

According to Charles Alexander, Allensworth’s mother, Phyllis, told him that he was named for Bishop Richard Allen, the respected preacher of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, whom she hoped her son would one day emulate. Allensworth must have taken this to heart, because, after experiencing a religious conversion, he became a minister during Reconstruction. Allensworth accomplished this by enrolling at the Baptist Theological Institute (now Roger Williams University) in Nashville, Tennessee, where he studied theology. And it was there that he met and married Josephine Leavell, an accomplished organist and music teacher.

Allensworth settled down to a quiet life in his native Louisville, where he preached from several pulpits. His mother, Phyllis, lived with them for a few months, until she passed away in 1878 at age 96, but joy filled the home once more when the couple had two children together named Eva and Nella. The success of Allensworth’s ministry also led to a political calling, and he served as a Kentucky delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1880 and 1884, being the first and only black delegate in Chicago both years. Back in his day, the Republican Party was synonymous with Abraham Lincoln and civil rights, and therefore attracted a considerable amount of blacks.

While life in Louisville was good, Allensworth was not allowed to rest on his laurels. In his book, Notable Southern Californians in Black History, author Robert Lee Johnson writes:

“In 1882, the United States military had two cavalry units and two infantry units that were segregated. One of the complaints was that there were not any black chaplains. A black soldier approached Reverend Allensworth to discuss the issue.”

Allensworth learned that the chaplain of the 24th Infantry (which was one of the Buffalo Soldier regiments) was planning to retire in four years. This caused him to spring into action. Allensworth embarked on a tireless campaign to win the support of Southern Democrats and Republicans in office, and then he sent letters to the Office of the Adjutant General (a chief army official) and President Grover Cleveland himself, laying out a persuasive argument for his cause. His efforts paid off, because on April 1, 1886, he was appointed as chaplain of the 24th Infantry by President Cleveland, with the rank of captain. He was one of only two black chaplains at the time, but for the next twenty years, Allensworth served faithfully in his new military role, while keeping a watchful eye on the men entrusted to his care.

Upon retiring in 1906, Allensworth attained the rank of lieutenant colonel, being the first black man in history to do so. He led his family to Los Angeles, but a quiet retirement was not in the equation for Allensworth. The country was still in the fierce grip of racial discrimination, under which blacks suffered. They were victims of disenfranchisement, segregation, and prevalent lynching. And Los Angeles, despite being part of a free state, was no exception. Allensworth sided with Booker T. Washington in his debate with W.E.B. Du Bois. Washington propagated the idea of blacks being self-sufficient and unified in a collective cause that was beneficial to the culture. While some of his views were controversial, Washington’s message also centered on blacks taking up agricultural pursuits as a colony, where they would be free of racial oppression.

“Upon retiring in 1906, Allensworth attained the rank of lieutenant colonel, being the first black man in history to do so.”

Other Los Angeles residents sympathized with Washington’s views as well, namely teacher and scholar William Payne, Nevada miner John W. Palmer, A.M.E. minister William H. Peck, and realtor Harry A. Mitchell. Allensworth joined forces with them, and together, the five “gentlemanly looking Negro men” (as the Delano Holograph labeled them on June 13, 1908) set out to create an all-black community in California.

Back then, whites who followed the logic of British scientist Francis Galton, creator of the field of eugenics² — a Greek word meaning “well-born” — believed that blacks were genetically inferior. Allensworth and his four colleagues were bent on countering the biological racism by establishing a town where blacks, particularly soldiers from the nation’s four all-black regiments, could enjoy opportunities denied them by systems and communities controlled by whites. In this agricultural colony, each soldier would have a decent home, where his family could live safely and in peace while he was off fighting for his country.

To make the dream a reality, on June 30, 1908, Colonel Allensworth and his associates created the California Colony and Home Promoting Association. Allensworth turned to the church community to raise the funds necessary for a land purchase, and while he succeeded in doing this, landowners refused to sell to him. In time, a white-owned Los Angeles land development syndicate known as Pacific Farming Company approached the eager buyer. About 30 miles north of Bakersfield lay 800 acres of fertile land in rural Solito, California that was up for sale. Not only did the Pacific Farming Company sell the land, the land deed they signed stated that they were to supply the future town with a water system equal to the needs of its residents.

On August 3, 1908, the association filed a township site plan with the Tulare County recorder for Solito, which had a convenient station that connected Los Angeles and San Francisco on the Santa Fe Railroad. That very year Solito was renamed “Allensworth” in honor of its most celebrated founder. A council form of government was chosen to administer town affairs. It was known as the Allensworth Progressive Association, of which both men and women held various positions of responsibility. Officers were routinely elected by townspeople, and during town meetings, residents were encouraged to participate in civic affairs.

The township attracted black families who moved there with enthusiasm. Within a year Allensworth was home to 35 families. By 1912, the population grew to 100, including the town’s first newborn, Alwortha Hall, who was born in 1910 to Allensworth residents William and Elizabeth Hall.³ In 1914, the town also became a voting precinct and a judicial district, with both a justice of the peace and constable. Two general stores, a post office, a library, and a school were established to serve the community. The school was the largest investment for the town, costing $5,000 to build. The one-room school offered classes catering to students ranging from elementary to high school grades, and it had three board members, one of which was Allensworth’s wife, Josephine, who was its first teacher.

An Allensworth business district soon developed, boasting a bakery, a livery stable, a drug store, a barber shop, a machine shop, several other stores, and even a hotel. But the town truly was an agricultural community, which depended on the cultivation of sugar beets, cotton, alfalfa, and grain. Black farmers also raised chickens, turkeys, dairy cattle, and Belgian hares. These enterprises required a lot of water, and for the first few years, the town flourished, with the population peaking at 300 settlers by the early 1920s.

The community started on a slow decline following a tragic incident in September, 1914. Colonel Allensworth sought to expand his eponymous town further. This involved a lecture circuit that took him to various black churches throughout California, where he spoke passionately to congregants in an effort to raise more funds and attract new residents. While in Monrovia, California to give one of his usual lectures, the Colonel stepped off a streetcar and was immediately struck down by a speeding motorcyclist. Unable to regain consciousness, the Colonel died within twenty-four hours. The Allensworth community was devastated, but it carried on under the leadership of the justice of the peace and co-founder Professor William Payne. The Colonel, however, could not be replaced.

By 1920, William Payne, who served as the school principal, was gone. He moved to El Centro for a teaching job. Allensworth’s widow, Josephine, moved to Los Angeles the same year to live with her daughter, Nella. After 1925 a mass exodus started when the Pacific Farming Company failed to supply enough irrigation water to meet the needs of Allensworth’s farmers, which led to prolonged legal battles. The water problem began in 1914, after a drought caused white farmers to close in on Allensworth and divert water from a community well. What used to be a well-watered area with water from the Sierra Nevada mountains simply bubbling up out of the earth soon suffered a drop in groundwater levels, which forced residents to drill. But the water eventually dried up. Residents were also forced to move away to find work, and property values in Allensworth bottomed out as a result. Even the racist Santa Fe railroad, which refused to hire blacks from Allensworth to man their own station, soon built a new line to bypass the town altogether.

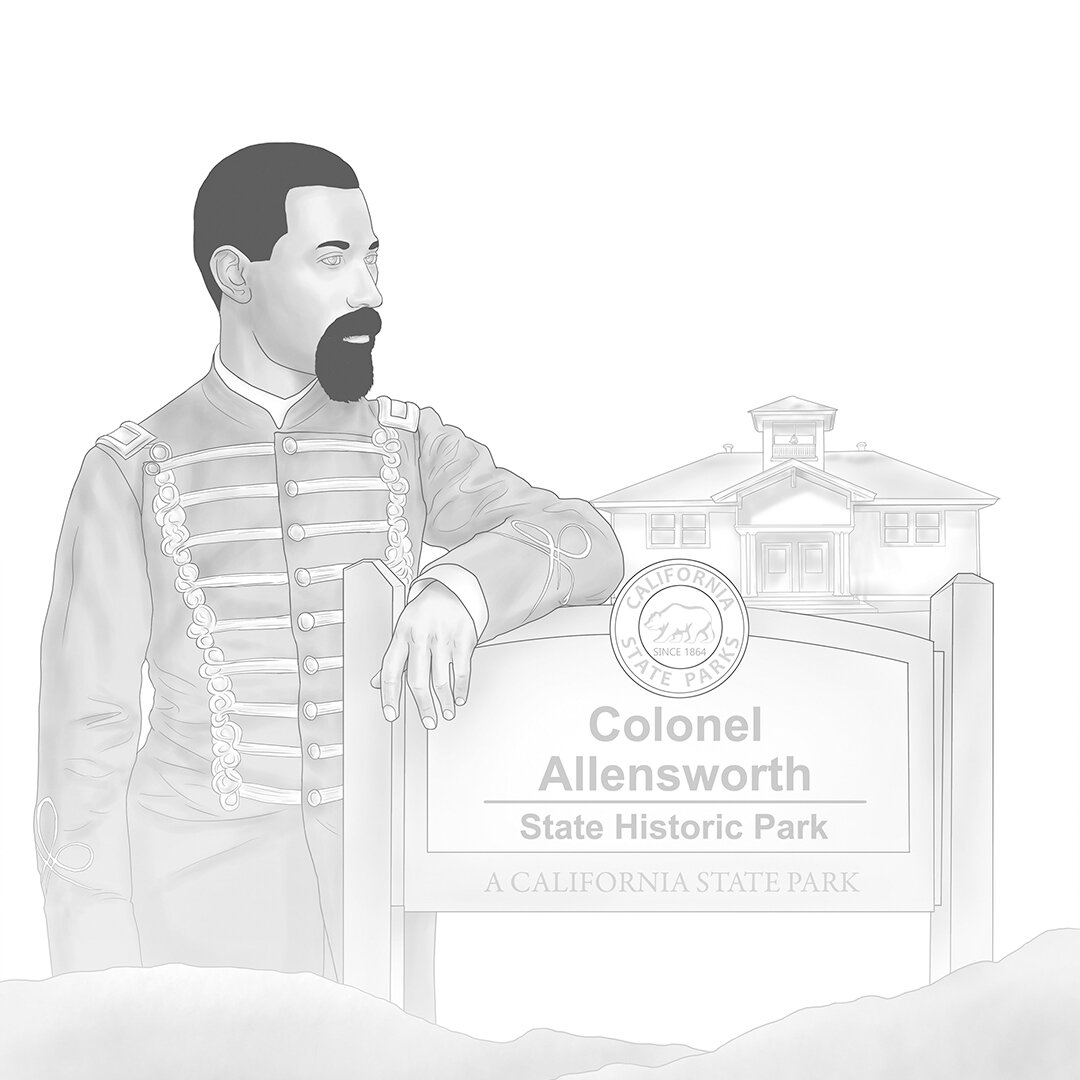

Then in 1966, State officials learned that the remaining groundwater was contaminated with arsenic. By that time, only 34 families remained in Allensworth, and all seemed lost. But in 1969, former Allensworth resident Cornelius “Ed” Pope — who was a draftsman and planner for the California Department of Parks and Recreation — launched a campaign to create a state historic site at Allensworth. By 1974, the state purchased the land and formed an advisory committee; and later that year, then-Governor Ronald Regan gave the go-ahead to establish the park. In 1976, plans for the development of the 240-acre park were approved, and on October 6, 1976, the park was officially dedicated.

Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park is on the National Registry of Historic Places and is a California Historical Landmark. Unlike many black communities of the past, which no longer exist, Allensworth can still be visited and experienced. The official website of the state park leaves us with this picture of Allensworth:

“Today a collection of lovingly restored and reconstructed early 20th-century buildings — including the Colonel’s house, historic schoolhouse, Baptist church, and library — once again dots this flat farm country, giving new life to the dreams of these visionary pioneers.”⁴

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in The Black History Activity Book.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Originating in Galveston, Texas with the June 19, 1865 announcement of General Order No. 3, former Texas slaves made a celebration out of the date and carried it wherever they migrated.