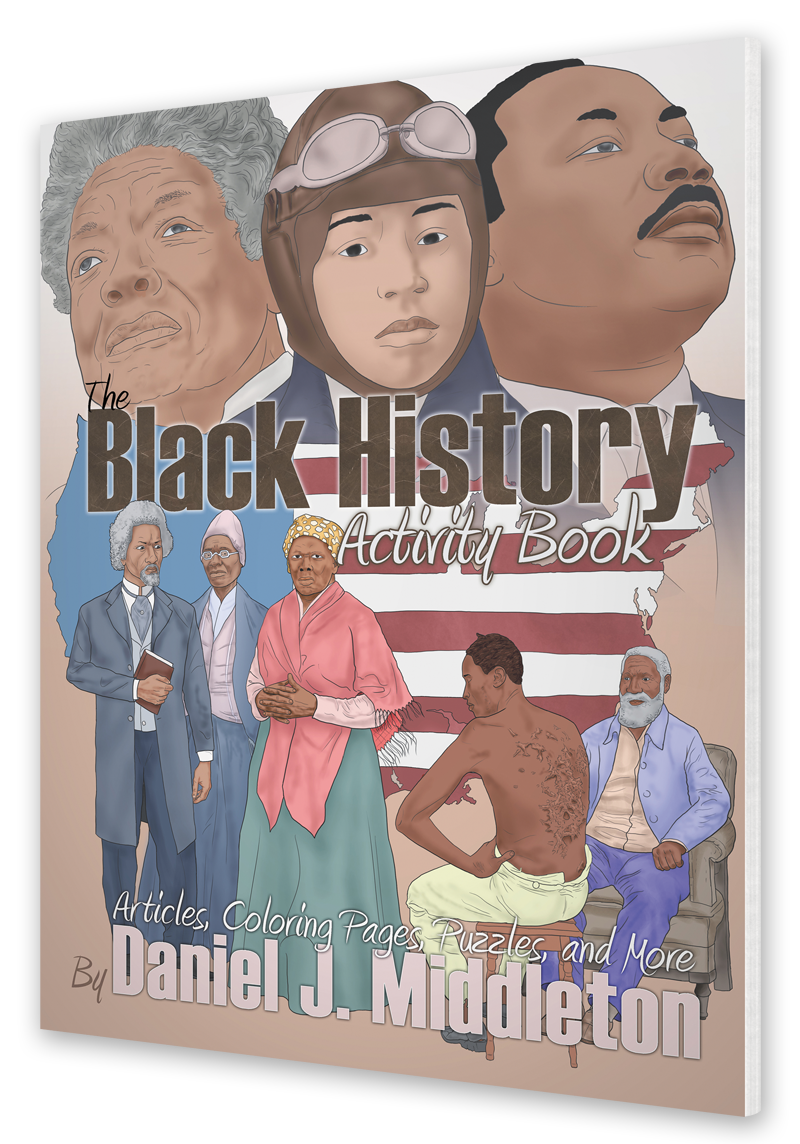

Janet Collins

The First Black American Prima Ballerina

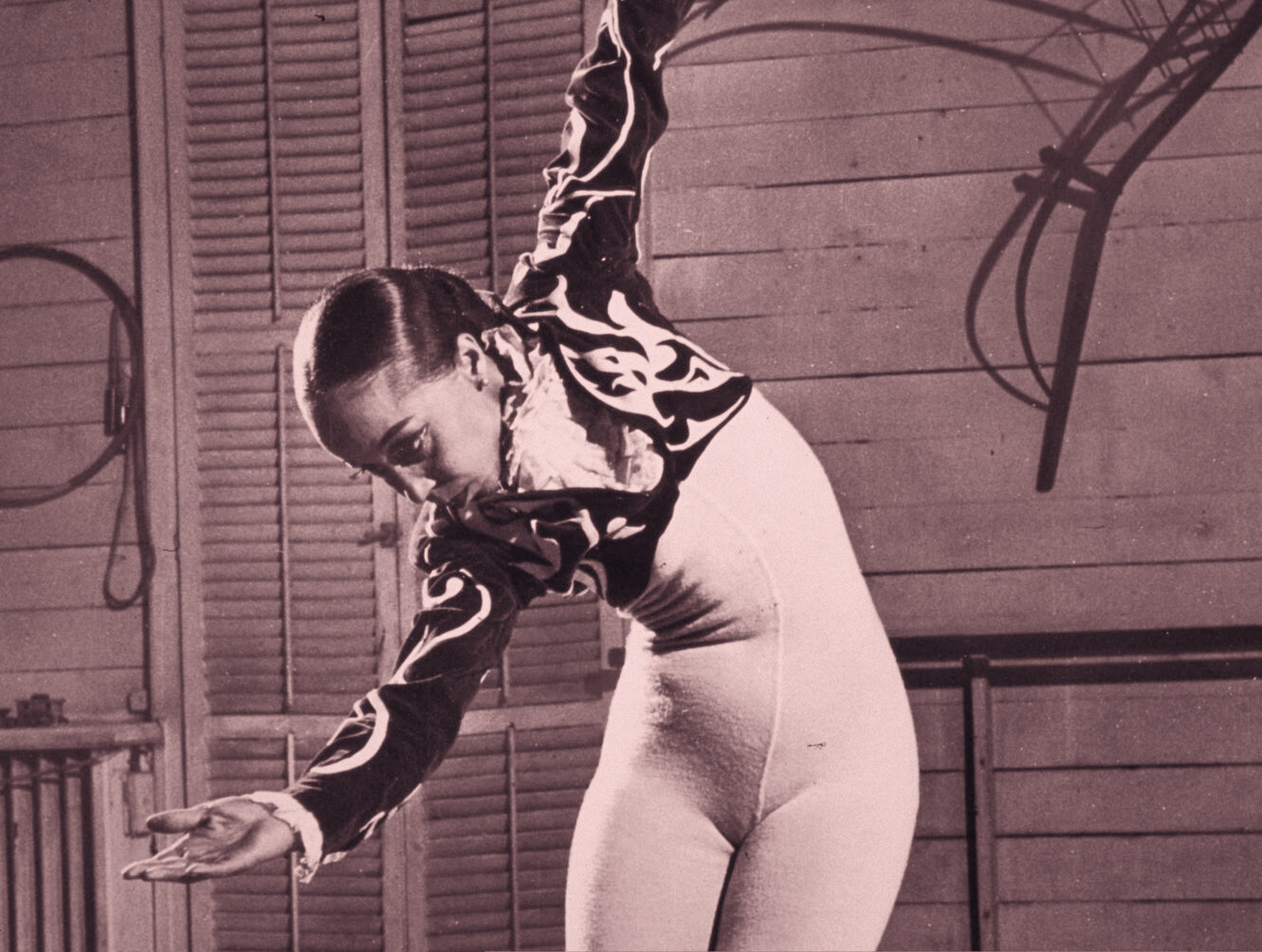

Initially intent on being a ballet dancer, Janet Collins was discouraged from the pursuit by professionals who considered her body and feet to be ill-suited for the art. This stigma plagued every black dancer in the 1930s. Yet Janet persisted, continuing with her dance lessons, and improving her skills until she reached a point where she felt herself capable enough to audition.

By age 15, a grand audition came. Lèonide Massine and the De Basil Ballet Russe Company beheld her graceful movements, which the other ballerinas applauded. Massine invited Janet to join the company, but with one significant caveat: she would have to dance in whiteface to hide the fact she was black.¹ Janet refused to do that. She politely declined, left the building, and cried profusely. From that moment on, Janet’s primary motivation was to improve her dancing, so that her talent would command more attention than her skin color.

“She would have to dance in whiteface to hide the fact she was black.”

Janet Collins entered the world in New Orleans, Louisiana, on March 7, 1917. By age four, her family moved to Los Angeles, where she attended classes at a Catholic community center. At age ten, she began studying ballet at the community center after classes. Among her instructors through the years were Mia Slavenska, Adolph Bolm, and the accomplished Carmelita Maracci, who was one of few dance teachers willing to accept black students at the time. Janet also studied modern dance with Lester Horton. Thus, she became equally adept in both modern and classical dance styles.

The exclusive nature of the European dance form, which the elites jealously guarded for generations, turned her parents against the idea of a career in dance. They encouraged Janet to become an artist instead. Janet partially acquiesced by attending Los Angeles City College, where she studied art on a scholarship. She later attended the Los Angeles Art Center School as well. During this time, dance remained her primary focus.

Following her audition for Lèonide Massine and the De Basil Ballet Russe Company, Janet performed in shows produced by the government-funded Negro Unit of the Federal Theatre Project. That included Hall Johnson’s Run, Little Chillun and the 1938 Chicago run of Swing Mikado. Janet also appeared in vaudeville shows while facing the cold rejection of the rarefied dance world she longed to enter. A big break came in the next decade, however. On the advice of a friend, Janet auditioned for Katherine Dunham and landed a spot in her black dance company. She appeared with the troupe in the 1943 20th Century Fox film Stormy Weather, which was considered one of the best musicals featuring a black cast. In keeping with the racist period, however, the film is marked by a small degree of minstrelsy, complete with Sambo depictions and blackface.²

Janet remained with Katherine Dunham for about two years before pursuing other opportunities. She spent three years in Los Angeles working on dances she choreographed. Her New York debut came in 1949, wherein she performed her signature choreography as part of a shared program at the 92nd Street YM-YWHA. Janet won some acclaim that year following two more solos. Dance Magazine praised her as:

“[T]he most outstanding debutante of the season.”

In time, Janet caught the eye of Zachary Solov while performing in Cole Porter’s Broadway production Out of this World. Solov was the ballet master of New York’s Metropolitan Opera House at the time, and upon seeing Janet’s lean elegance and polish, he invited her to join the Metropolitan Company.

Janet Collins succeeded in breaking a crucial color barrier when she performed in a production of Aida in November of 1951. In the following year, she joined the Met’s corps de ballet, cementing her as its first black prima ballerina. Her career with the Met took her on tours through the South, where she faced racism. But Janet danced for the Met until 1954. Janet eventually devoted herself to teaching ballet and choreographing performances. Being a devout Catholic, she infused her dance lessons with religious themes. One of her quintessential dances, performed at New York’s Marymount Manhattan College in 1965, was based on the creation chapters of the book of Genesis. In the final two decades of her life, she focused on painting religious subjects,³ but her legacy in the dance world remains as strong as ever.

____________________

Learn more about Janet Collins by reading Night’s Dancer.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in The Black History Activity Book.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

Sheku Kanneh-Mason is a young British cellist who was the first black person to win BBC Young Musician of the Year in 2016. He also became the first cellist to chart in the UK in the Top 10.