Ann Lowe

The Invisible Couturier Who Dressed America’s Elite

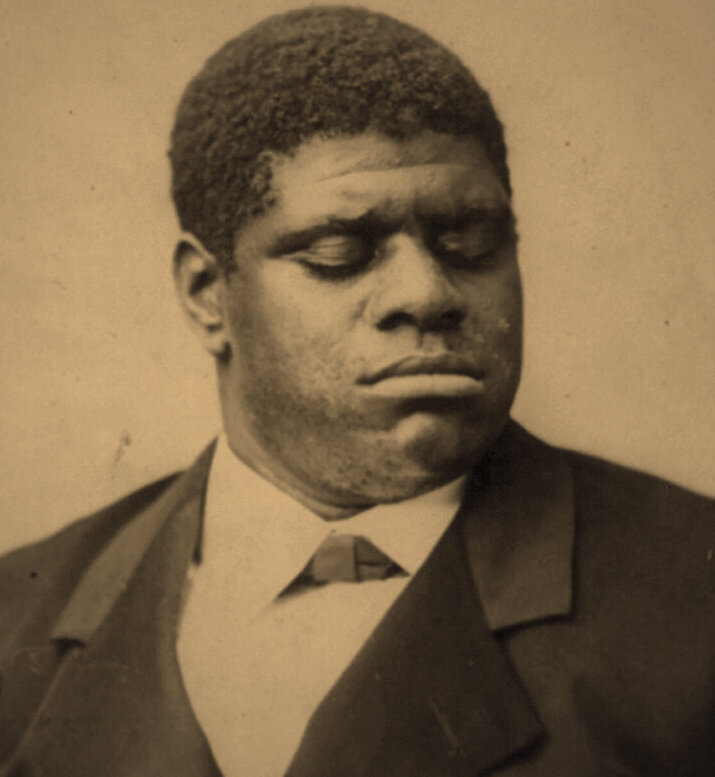

A portrait of Ann Lowe in her later years.

When Jacqueline Bouvier walked down the aisle on September 12, 1953, to marry Senator John F. Kennedy, she wore one of the most photographed wedding dresses in American history. Made from fifty yards of ivory silk taffeta with intricate tucking and delicate wax flowers, the gown would become an icon of mid-century elegance. Yet when reporters asked who designed the stunning creation, the future First Lady reportedly answered dismissively: “a colored dressmaker did it.” That “colored dressmaker” was Ann Lowe, the first black woman to become a noted fashion designer in America, and the creative genius behind some of the most exquisite gowns ever worn by the nation’s social elite.

Lowe’s story is one of extraordinary talent flourishing despite crushing discrimination, of a woman who rose from the poverty of post-Reconstruction Alabama to dress the Rockefellers, du Ponts, and Roosevelts. Her fairytale-like gowns appeared repeatedly in Vogue and Vanity Fair magazines and were worn by women in the highest levels of American society. Yet for most of her fifty-year career, she remained “society’s best kept secret,” as the Saturday Evening Post called her in 1964—invisible to the public eye while her creations dazzled at the most exclusive social events of the century.

From Alabama Cotton Fields to Fashion Design Dreams

Ann Cole Lowe was born in Clayton, Alabama, around 1898, the great-granddaughter of an enslaved woman and an Alabama plantation owner. Her grandmother Georgia Thompkins and mother Janie Cole Lowe had been domestic slaves in Alabama in the 1850s until Ann’s grandfather, General Cole, a freeman carpenter, purchased and gained their freedom in 1860. In the shadow of slavery’s legacy, these women built something remarkable: a thriving dressmaking business that served wealthy white families in the state.

Young Ann learned to sew at age five, and by six, she had developed a fondness for using scraps of fabric to make small decorative flowers patterned after the flowers she saw in the family’s garden. This childhood pastime would later become her signature, appearing on gowns worn by debutantes and society matrons across the nation. By age ten, she was making her own dress patterns. The artistry was in her blood, but so was the burden of race in a South governed by Jim Crow laws.

When Lowe was sixteen, her mother unexpectedly died in 1914, leaving behind four unfinished ball gowns for a New Year’s Eve celebration—at least one of which belonged to the first lady of Alabama. Young Ann stepped forward to complete the order, her needle steady despite her grief. Lowe’s successful completion of the gowns helped establish her as a skilled dressmaker in the state. It was her first taste of serving the elite, and it would not be her last.

At fourteen, Lowe married Lee Cohen, with whom she had a son, Arthur Lee. Her husband, ten years her senior, wanted her to focus on being a wife and mother. Initially, Lowe complied, setting aside her needles for domesticity. But a pivotal moment came in 1916 when Josephine Edwards Lee, a wealthy Tampa socialite, spotted her in an Alabama department store. Mrs. Lee observed that Lowe’s outfit was very stylish and exceptionally well-made. When Lowe informed her that she made the ensemble herself, Lee invited her to Florida as her live-in dressmaker to create bridal gowns and trousseau (the traditional bridal wardrobe and household linens) for her twin daughters.

Despite her husband’s objections, Lowe accepted the offer. She felt it was a chance to make all the lovely gowns she’d always dreamed of. In 1917, Lowe and her young son moved to the Lee family estate at Lake Thonotosassa in Tampa, leaving behind the constraints of an unsupportive marriage for the promise of artistic freedom.

Education and Career of a Pioneering Black Fashion Designer

The wealthy Tampa clients who discovered Lowe’s talents encouraged her to pursue formal training. In 1917, they enrolled her at the S.T. Taylor Design School in New York City. But when Lowe arrived at the prestigious institution, she was met with a harsh reality: she was shunned by the school’s director because of her race. He allowed her to attend the school, but segregated her in another classroom because her classmates refused to be in the same space with a black American.

The sad irony was that Lowe’s design abilities were far superior to her classmates, and her creations were used as models of exceptional work for the other students. Accustomed to forging her own path, Lowe graduated in half the required time. She returned to Tampa with a diploma earned in solitude but armed with technical skills that would elevate her natural talent to new heights.

Gasparilla balls are elaborate formal social events that are part of Tampa’s annual Gasparilla festival, which celebrates the legendary pirate José Gaspar (Gasparilla). The festival includes parades, parties, and fancy dress balls where Tampa's elite society attend in lavish gowns.

Around 1920, she opened her first dress salon, the Annie Cone boutique. The shop catered to Tampa’s high society, and Lowe’s reputation spread like wildfire among the wealthy women who attended elaborate Gasparilla balls and social events. From 1924 to 1929, dressing the elite women who attended the Gasparilla balls was a primary source of creative expression for Lowe. Each gown was a masterpiece, adorned with her signature fabric flowers that looked so lifelike they seemed to have been plucked from nature itself.

By 1928, Lowe had saved an impressive $20,000—nearly $300,000 in today’s currency. With this nest egg, she permanently relocated to New York City in 1928. She arrived with grand dreams of dressing Manhattan’s most fashionable women, but her timing was catastrophic: the stock market crashed in 1929, plunging the nation into the Great Depression.

When Lowe arrived in New York, she rented a workspace at West 46th Street, where she struggled to cultivate patrons. By 1929, she had exhausted her funds. For the next two decades, she was forced to work anonymously for other fashion houses, her creative genius hidden behind white-owned labels. She worked on commission as a seamstress and designer at some of the top department stores: Neiman Marcus, Chez Sonia, Henri Bendel, and Saks Fifth Avenue, yet was consistently unrecognized for her labor.

In 1946, Olivia de Havilland wore a dress by Lowe to accept her Best Actress Oscar for her performance in To Each His Own. Lowe received no credit for the design; the name on the gown was Sonia Rosenberg. This pattern of erasure would plague Lowe throughout her career—her hands created the beauty, but others claimed the glory.

The Woman Who Made Jackie Kennedy’s Iconic Wedding Dress

In 1950, determined to claim her rightful place in the fashion world, Lowe and her son Arthur Lee opened a new dress shop, Ann Lowe’s Gowns, on Lexington Avenue with the express goal of bolstering her reputation as a designer and seamstress. Finally, her name would be on the label. The salon was an immediate success, attracting clients whose names appeared in the Social Register—the Rockefellers, du Ponts, Posts, Biddles, and Auchincloss families.

Portrait of Jacqueline Bouvier in the 1940s.

Janet Auchincloss had been a client since 1942, when Lowe designed her wedding dress for her marriage to Hugh Auchincloss. So when Janet’s daughter Jacqueline Bouvier needed a wedding dress for her marriage to the ambitious young Senator John F. Kennedy, there was never any question about who would design it.

The commission came with extraordinary pressure. The groom’s father—the famously domineering Joseph Kennedy—was involved in every detail of wedding planning, including the dress. Jackie had just returned from Paris, and she wanted something simple and French, but the Kennedy patriarch would not have it. Lowe and her assistants spent two months cutting and sewing the ornate folds of the gown out of more than fifty yards of silk taffeta.

Lowe’s dress for Jacqueline Bouvier was described by the New York Times as consisting of fifty yards of “ivory silk taffeta with interwoven bands of tucking forming the bodice and similar tucking in large circular designs swept around the full skirt.” The creation was magnificent—a testament to Lowe’s unparalleled craftsmanship and eye for detail.

Then disaster struck. Ten days before the wedding, a water line broke and destroyed not just the wedding gown, but the bridesmaids dresses too. What then ensued was an all-hands on deck mission to recreate everything with new fabric, working day and night to complete Lowe’s designs in time for the historic nuptials. Repurchasing the fabric and working all hours turned a projected profit into a $2,200 loss for Lowe. Not only did the designer suffer a monetary loss from the experience, she also reportedly never told the bride or her mother about the mishap.

Upon arriving in Newport to deliver the dresses, the house staff would not let her enter through the front door. Lowe declared that she would leave and take the dresses with her. She walked through the front door. Her dignity would not be compromised, even at such a crucial moment.

The wedding was a sensation, covered by newspapers across the nation. The gown was described in detail in the New York Times and other publications, but Lowe received no credit for her work. Years later, when questioned about the famous dress, the popular narrative claimed that Jackie Kennedy had referred to Lowe as “a colored dressmaker.” However, fashion historians have since revealed that this dismissive phrase actually came from a 1961 Ladies’ Home Journal article, not from Kennedy herself. When Lowe, believing Kennedy had referred to her that way, wrote her a letter “to tell you how hurt I feel” about the apparent snub, an assistant to the first lady soon responded apologetically, explaining the snub was the magazine’s, not Jackie’s.

Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy’s iconic 1953 wedding dress, designed by Ann Lowe, was a masterpiece of the era’s “New Look.”

Ann Lowe on Madison Avenue: Breaking Barriers in Fashion

Despite the lack of public recognition, Lowe’s business flourished in the 1950s. She opened and operated several shops in Manhattan’s wealthiest neighborhoods during a time when black-owned businesses were scarce, particularly within the highly segregated fashion industry. The Madison Avenue locations solidified Lowe as the first black American to have a shop on the famed fashion retail strip.

But Lowe’s generosity and poor business sense worked against her. Throughout her career, she continued to work for wealthy clientele who often talked her out of charging hundreds of dollars for her designs. After paying her staff, she often failed to make a profit on her creations. Lowe later admitted that at the height of her career, she was virtually broke. She was too frequently persuaded by customers to sell her luxurious designs at a fraction of their costs.

An atelier is a fashion designer’s workshop or studio where custom garments are made. It’s typically where high-end couture work happens, the workspace where designers and their seamstresses create one-of-a-kind pieces. The word comes from French and literally means “workshop.” In fashion, it refers specifically to the creative workspace of a couturier, often implying a more prestigious or artistic environment than just calling it a “shop” or “salon.”

In the context of Ann Lowe, using “atelier” emphasizes the high-end, custom nature of her work and positions her as a serious couturier rather than just a dressmaker.

Tragedy struck in 1958 when Arthur Cone was killed in a car accident. Lowe lost not only her beloved son but also her business partner and financial manager. Her tax payments fell into arrears, and in 1960 she closed her atelier due to debt. Adding to her woes, she developed glaucoma in her right eye, causing pain and disrupting her work.

In 1962, the IRS closed Lowe’s New York shop due to $12,800 owed in back taxes. That same year, her right eye was removed due to glaucoma. In 1963, she declared bankruptcy. It seemed as though the woman who had dressed America’s most privileged families was destined to end her career in financial ruin.

But then something remarkable happened. While she was recuperating, an anonymous friend paid Lowe’s debts that enabled her to work again. She believed the debt was later paid by Jacqueline Kennedy. When the legendary seamstress died at the age of 82, she was relatively unknown. “Ann always felt it was Mrs. Kennedy, and I like to think it was and that she did so because she had learned of the wedding dress disaster and Ann’s integrity in righting the situation,” says Julia Faye Smith, her biographer.

The Legacy of Ann Lowe: Recognition for a Forgotten Fashion Pioneer

Lowe’s final chapter was marked by both recognition and decline. Soon after her bankruptcy, she developed a cataract in her left eye, though surgery was able to save her sight. In 1968, she opened a new store, Ann Lowe Originals, on Madison Avenue. The 1960s brought her some of the acclaim she had long deserved—Ebony magazine called her “The Dean of American Designers” in 1966, and she was finally profiled in major publications.

While fashion became less formal during the 1960s, Lowe’s work remained in demand. She outfitted eighty-five debutantes in 1967 alone. But her failing eyesight had become so severe that she was forced to retire in 1972.

In the last five years of her life, Lowe lived with her daughter Ruth in Queens. She died at her daughter's home on February 25, 1981, at the age of 82, after an extended illness. The woman who had created gowns worn to presidential inaugurations, Academy Award ceremonies, and the most exclusive debutante balls in America passed away largely unknown and broke.

Yet Ann Lowe’s legacy refuses to be erased. A collection of five of Ann Lowe’s designs is part of permanent archives at the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Three are on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Fashion scholars now recognize her as a pioneering artist whose technical brilliance rivaled that of any couturier of her era.

“That dress she made for Jackie Kennedy was widely photographed. A lot of people saw it and it no doubt influenced average American wedding dresses and ball gowns,” said Elizabeth Way, an assistant curator at The Museum at FIT. “The fact that (the dress) came from the creativity of a Black woman really speaks to how instrumental Black people have been in shaping American culture.”

Lowe’s story is one of both triumph and tragedy—a testament to what extraordinary talent can achieve despite systemic barriers, and a sobering reminder of how racism can steal recognition from those who deserve it most. She navigated a white world that simultaneously needed her artistry and denied her humanity, creating beauty for those who often refused to see her as their equal.

In an era when black women had few paths to economic independence, Ann Lowe carved out a space for herself among America’s elite through sheer force of will and uncompromising artistic vision. Her signature fabric flowers, painstakingly crafted by hand, were more than decorative elements—they were symbols of resilience, blooming against all odds in a garden where she was never meant to grow.

Today, as a new generation discovers her story through books, museum exhibitions, and an upcoming biographical film produced by Serena Williams and Ruth E. Carter, Ann Lowe is finally receiving the recognition that eluded her in life. Her legacy reminds us that behind every beautiful thing, there is often an invisible hand—and that hand deserves to be seen, celebrated, and remembered.

The next time you see a bride walking down the aisle in an exquisite gown, remember Ann Lowe. Remember the black woman who transformed fifty yards of silk taffeta into one of the most iconic dresses in American history, then disappeared back into the shadows, her name erased from the very story she helped create. Her fingers may have stilled, but her flowers—those delicate symbols of beauty persisting against impossible odds—continue to bloom in the gardens of fashion history, demanding that we finally see the invisible artist who planted them there.

Julia López, an award-winning self-taught painter, usually paints in the Naïve genre, which calls for childlike simplicity. Her work often depicts rural and coastal life in Mexico.