Augusta Braxton Baker

The Trailblazing Curator Who Revolutionized Children’s Books

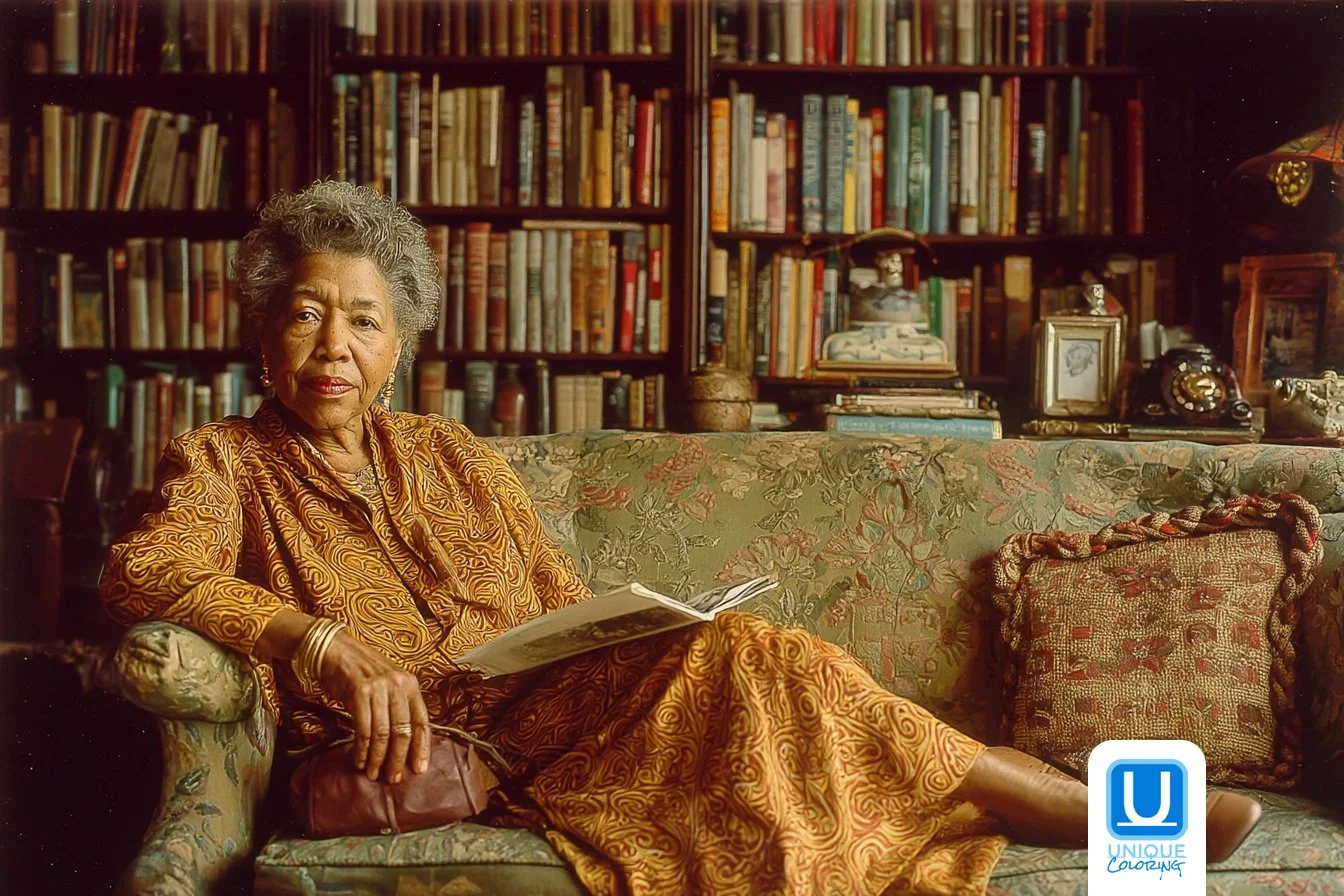

Portrait of Augusta Braxton Baker relaxing in her home library.

In the dusty halls of Harlem’s 135th Street Branch Library in 1937, a young black woman named Augusta Braxton Baker lit her first storytelling candle and unknowingly ignited a revolution. She would become the first black woman to hold an administrative position at the New York Public Library, transforming children’s literature from a landscape riddled with racist stereotypes into one that celebrated the dignity and complexity of black life. When Baker died in 1998, she left behind not just a collection of thousands of carefully curated books, but an entirely new vision of what children’s literature could be—one where every child could see themselves reflected with respect and wonder.

Her revolutionary James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection became a catalyst in public library collection development, pushing publishers to improve their offerings and encouraging the creation of books with better representations of black life. But Baker’s influence stretched far beyond library shelves. She consulted for Sesame Street during its early years, helped train generations of librarians, and authored multiple storytelling guides that are still used today. Through her tireless advocacy, she didn’t just change what children read—she changed how an entire industry thought about black stories.

Early Life: Where Stories Begin

Augusta Braxton was born on April 1, 1911, in Baltimore, Maryland, to parents who were both schoolteachers. Her very name carried the weight of storytelling tradition—she was named after her grandmother, Augusta Fax, who cared for her during the day while her parents worked and filled her world with stories. Baker delighted in these stories, carrying her love for them throughout her life.

The Braxton household was one where education reigned supreme. She learned to read before starting elementary school, later enrolling in the (racially segregated) black high school where her father taught, and graduating at the age of 16. Even at such a young age, Baker’s intellectual gifts were undeniable—but her grandmother’s oral storytelling tradition would shape her life’s mission in ways she couldn’t yet imagine.

Baker then entered the University of Pittsburgh, where she met and married James Baker by the end of her sophomore year, transferring to the New York College for Teachers in Albany, New York. The young bride was determined to continue her education, even as social expectations of the era suggested otherwise.

Baker received a B.A. (1933) in education and a B.S. (1934) in library science from that institution. Eleanor Roosevelt, then the first lady of New York, intervened and opened the door for black students to attend New York State College, from which Baker would graduate. Shortly thereafter, the Bakers moved to New York City, where Augusta would begin a career in revolutionizing children’s literature.

The Harlem Library Years: Confronting Literary Racism

Baker worked for a few years as a teacher, but in 1937 she became a children’s librarian at the 135th Street Branch (now the Countee Cullen Regional Branch) of the New York Public Library in Harlem. It was supposed to be a temporary job. It lasted 17 years.

What Baker discovered in those early days was both heartbreaking and infuriating. The library primarily served Harlem’s African American community, yet the children’s books on its shelves rarely reflected the lives and realities of black children. Worse, when black characters did appear, they were often portrayed in demeaning and harmful ways. Appalled by the depiction of black characters in the fiction then available to black children, Baker struggled to amass a collection of books that would provide inspiring black role models while at the same time presenting an accurate view of African-American life to young Americans of all races and backgrounds.

Early on, she recognized the lack of positive role models in children’s literature for young African American readers. She identified and removed from the library shelves books that depicted black characters as lazy, ill-spoken, or illustrated with distorted body features. This wasn’t simply about censorship—it was about dignity. Baker understood that children’s earliest encounters with literature shaped how they saw themselves and their place in the world.

Building the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection: A Revolutionary Act

Librarian Augusta Baker shares Ellen Tarry's “Janie Belle” with a young reader at the library in 1941. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The project, begun in 1939, culminated in the branch’s James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection, a body of children's books selected for their unbiased, accurate, well-rounded picture of black life in all parts of the world. In a 1943 article, Baker stated her criteria for selection, explaining that the books should give a comprehensive view of black experiences.

This wasn’t merely a reading list—it was a manifesto. Every book she selected had to meet her rigorous standards for authentic representation. Baker’s dedication to this cause helped produce children’s authors of the sort she was looking for, as well as publishers eager to publish them.

Baker also initiated a number of new services and programs, including concerts, reading clubs, and guest appearances by black artists, writers, diplomats, and other role models. She understood that literature existed within a broader cultural ecosystem and worked to create spaces where black children could see successful black adults who looked like them.

The Art of Storytelling: Finding Her Voice

In time, Baker discovered her gift for storytelling, and so did the NYPL. Her grandmother's folktales reached the ears of Harlem children through Baker's voice. Baker had grown up listening to her grandmother's stories, and now she was creating her own storytelling tradition to continue that legacy.

First, she would light a candle and then tell a story. During her lifetime, the late Augusta Baker introduced children to literature through dramatic storytelling that directed those she entertained to the world of books. This simple ritual—the lighting of a candle before each story—became Baker’s signature, transforming ordinary library visits into extraordinary experiences.

In 1953, she was appointed storytelling specialist, and two years later, The Talking Tree, the first of what would be four collections of stories by Baker, was published. Her storytelling wasn’t just entertainment; it was education, empowerment, and cultural preservation all rolled into one.

Rising Through the Ranks: Breaking Administrative Barriers

In 1953, Baker was appointed Assistant Coordinator for Children’s Services, making her the first African American librarian in an administrative position at The New York Public Library. A promotion in 1961—to the highest position within the city library system held by an African-American to that date—made Baker coordinator of children’s services in all 82 branches of the NYPL.

This promotion wasn’t merely symbolic—it gave Baker the platform she needed to implement her vision across the entire New York Public Library system. She would remain in this role until her retirement in 1974. During those 13 years, Baker strengthened the library’s collection by adding audiovisual materials and, in the process, brought her vision to the outside world.

Her influence extended far beyond New York. She chaired the committee that awarded the Newbery Medal and the Caldecott Medal, giving her direct input into which books received the highest honors in children’s literature. Through this role and her position at NYPL, she influenced the careers of many children’s authors and illustrators, including Ezra Jack Keats, Madeleine L’Engle, Maurice Sendak, and John Steptoe.

Publishing Her Vision: Advocating for Black Children’s Literature

In 1957, Books About Negro Life for Children, the bibliography of the collection, was published; it contained hundreds of book titles. This wasn’t just a catalog—it was a roadmap for parents, teachers, and librarians seeking quality literature that portrayed black children with dignity and complexity.

The lists and the standards were freely distributed from the 135th Street Branch in Harlem. Many librarians, editors, and authors used the lists with their own work. Baker created new industry standards, one carefully vetted book at a time.

In 1971, the biography was retitled The Black Experience in Children’s Books, and its criteria played an important part in bringing awareness about harmful stereotypes in Helen Bannerman’s The Story of Little Black Sambo. The renaming reflected the changing times and Baker’s evolving understanding of how language shapes perception.

Expanding Her Influence: From Sesame Street to South Carolina

Baker became a consultant to television’s Sesame Street and began teaching and lecturing extensively on storytelling and children’s literature. She maintained that presence by giving speeches at international workshops and conferences. Her influence on Sesame Street helped ensure that one of America’s most beloved children’s programs would reflect the diversity she had long advocated for in literature.

In 1963, President John F. Kennedy invited her to the White House to discuss civil rights issues in education and children’s services. This invitation demonstrated how Baker’s work had transcended library walls to become part of national conversations about equality and education.

She produced several reference guides for storytellers, including Stories: A List of Stories to Tell and to Read Aloud, The Talking Tree, and Golden Lynx. In November of that year, she also began a series of weekly broadcasts, The World of Children’s Literature, on WNYC-Radio. Each publication extended her reach, training new generations of storytellers in her methods and philosophy.

The University Years: A New Chapter in South Carolina

In 1974, Baker retired from the New York Public Library. However, in 1980, she returned to librarianship to assume the newly created Storyteller-in-Residence position at the University of South Carolina—the first such position in any American university. At age 69, when many would consider slowing down, Baker was pioneering yet another first.

For the next 14 years, she traveled around South Carolina giving storytelling workshops and collaborating with county libraries. She remained there until her second retirement in 1994. Even in her eighties, Baker continued to champion the cause that had defined her life, ensuring that all children had access to stories that affirmed their humanity.

During her time there, Baker co-wrote a book entitled Storytelling: Art and Technique with colleague Ellin Greene, which was published in 1987. This comprehensive guide to storytelling became a foundational text for librarians and educators, codifying the techniques Baker had perfected over decades of practice.

Awards and Recognition: A Legacy Acknowledged

Throughout her career, Baker received numerous honors that reflected the profound impact of her work. Among Baker’s many accolades were two honorary doctorates, the Grolier Foundation Award, the Regina Medal from the Catholic Library Association, and the Constance Lindsay Skinner Award from the Women’s National Book Association.

In 1989, she became the first Zora Neale Hurston Award recipient, presented by the Association of Black Storytellers. This award was particularly fitting, honoring Baker and the legacy of Zora Neale Hurston, another groundbreaking figure who fought to preserve and celebrate black storytelling traditions.

Baker, named No. 6 on the list of the 100 most important library figures in our nation’s history, is best known for her work in the New York City Public Library System. This recognition placed her among the most influential librarians ever, acknowledging her role in fundamentally changing the profession.

Final Years and Lasting Impact

After a long illness, Augusta Braxton Baker died on February 23, 1998, at 86 in Columbia, SC. Her death marked the end of an era, but her influence continues to ripple through libraries, schools, and publishing houses nationwide.

Her legacy has remained even today, particularly through the Baker’s Dozen: A Celebration of Stories annual storytelling festival. Sponsored by the University of South Carolina College of Information and Communications and the Richland County Public Library, this festival originated in 1987 during Baker’s time at the University and is celebrated today.

The Augusta Baker Collection reflects her deep interest in storytelling, children’s literature, and librarianship. Donated by her son, James H. Baker III, the collection contains over 1,600 children’s books, papers, illustrations, and anthologies of folktales Baker used during her career.

In 2011, the College of Information and Communications created the Augusta Baker Endowment Chair. Dr. Nicole A. Cooke was appointed to this position in 2019, ensuring that Baker’s commitment to diversity in library science continues to influence new generations of librarians.

Her Philosophy Lives On

When asked what she told her students when she conducted her workshops, Baker stated in a 1995 Horn Book interview: “I tell them what I've always said. Let the story tell itself, and if it is a good story and you have prepared it well, you do not need all the extras — the costumes, the histrionics, the high drama.”

In 2024, Penguin Random House published Go Forth and Tell: The Life of Augusta Baker, Librarian and Master Storyteller, a children’s book chronicling her background and career. The publication of this biography for children ensures that Baker’s story will inspire future generations of young readers and storytellers.

Augusta Braxton Baker’s life was a testament to the transformative power of stories. She understood that the books children read in their earliest years shape not just their literacy, but also their sense of self and possibility. By fighting for authentic, dignified representation in children’s literature, she didn’t just change library collections—she changed lives. Her candle may have been extinguished, but the light she kindled continues to illuminate pathways for children of all backgrounds to see themselves as heroes in their own stories.

J. Drew Lanham is an avid birder, Master Teacher, and Certified Wildlife Biologist who teaches wildlife ecology at Clemson University.