Frederick McKinley Jones

The Black Genius Who Invented Portable Refrigeration

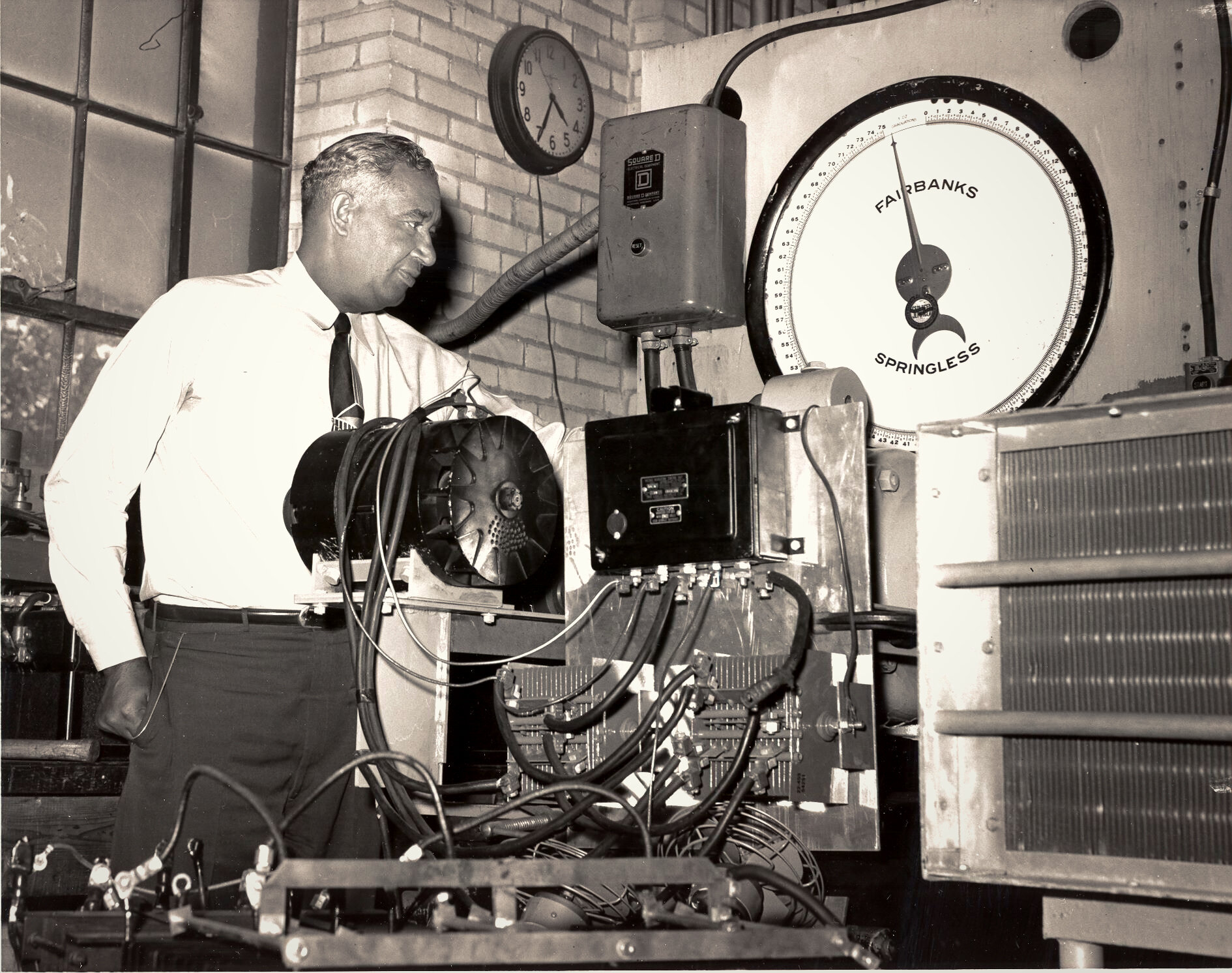

One of the most prolific inventors in America is someone few Americans — and people around the world for that matter — have heard of. He is a black Midwesterner by the name of Frederick McKinley Jones, who just so happened to invent refrigeration equipment that makes a child’s routine trot to the ice cream truck possible. The frozen aisle at your local grocer remains stocked largely because of Jones as well. But his innovations didn’t stop there. Jones would eventually be awarded 61 patents in his lifetime, 40 for refrigeration equipment, and 21 others for diverse inventions ranging from portable X-ray machines to movie theater ticket dispensing machines, gasoline engines, window air conditioning units, and ice cream making machines.

Frederick McKinley Jones was born in Covington, Kentucky — across the river from Cincinnati, Ohio — on May 17, 1893. His father John Jones was white — an Irishman by blood — but his mother was black. This essentially meant Jones was black, since, some 40 years earlier, he would have been a slave in the fields of Kentucky due to his “mulatto” status — a term introduced to us by novelist Lydia Maria Child.¹ Jones’s parents barely figured in his life. His mother died while he was still a toddler,² and a biography of Jones titled I’ve Got an Idea! by authors Gloria Swanson and Margaret Ott reveals that his father struggled to raise him until the age of seven, at which time the elder Jones sent him to a Catholic rectory.

By age nine, both his parents were dead, but a Catholic priest in Kentucky named Father Ryan took him in and saw to his early education by enrolling him in elementary school. That situation lasted less than two years, since Jones would rather fix things than sit in a stuffy schoolroom. When he was 11, Jones left school, ran away, and soon after found work as a janitor at R.C. Crothers Garage in Cincinnati.

“[A]t a mere 14 years of age, they hired him as a full-time mechanic. Within another year he became foreman.”

He developed an interest in auto mechanics on the job by watching men work on cars. Jones was soon trusted to tinker with autos as well and was a promising and skilled teen at the trade, because, at a mere 14 years of age, they hired him as a full-time mechanic. Within another year he became foreman. His mechanical mastery was largely self-taught, being derived in part from his many hours spent reading books. He also had another interest in autos. According to the Minnesota Science & Technology Hall of Fame:

“As a sideline, he designed race cars for the shop’s owner to be run on the local racing circuit.”

But Jones longed to be behind the wheel. Denied that opportunity by his boss, he decided to race cars on company time and was fired at age 17. This led Jones to the South, where he landed odd jobs here and there. He experienced racism like many other black men of the day and found it hard to secure decent work. Knocking on the doors of homes and businesses and offering labor in exchange for a meal kept him alive. A paying job would turn up on occasion, each one taking him to a different part of the country — a stint on a sightseeing paddle steamer in St. Louis that saw him feeding coal into a firebox; another brief stint as a mechanic in Chicago at a Cadillac garage — the list goes on.

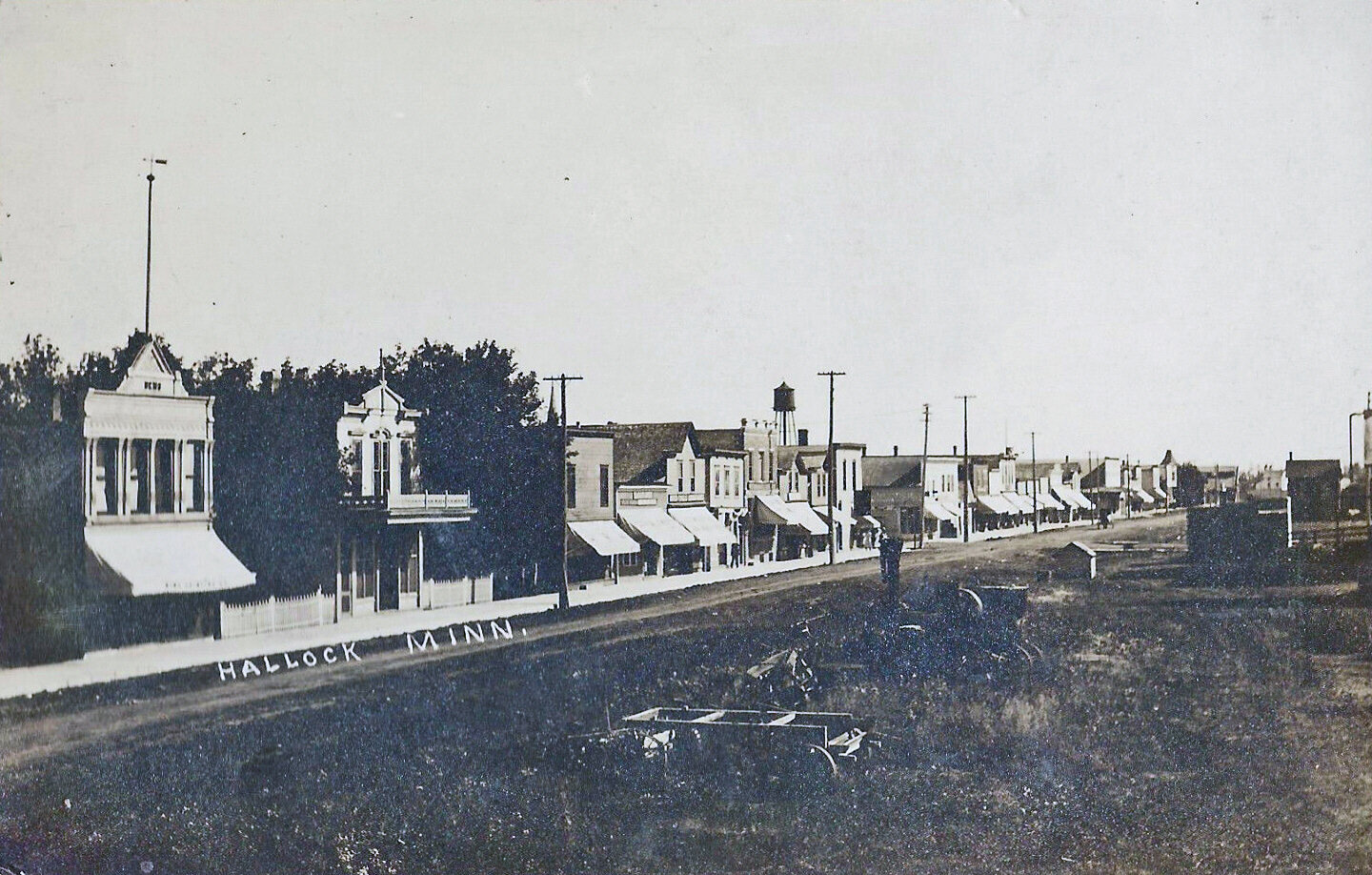

One job he landed in Minneapolis, Minnesota eventually led to his greatest opportunity. Jones found work at a hotel as a janitor and boiler repairman. His apparent mechanical skills caught the eye of a hotel guest named Oscar Younggren, who, after watching Jones fix a boiler offered him a better job. Jones traveled about 400 miles to Hallock in Minnesota’s Red River Valley to fill his new post, that of master mechanic on a 50,000-acre farm. Owned by railroad tycoon James J. Hill, the farm, named Humboldt, was eventually split off, with 3,000 acres being managed by Hill’s youngest son, Walter.³ They named the new farm Northcote, of which the Minnesota Historical Society writes:

“Northcote was a 3,000-acre bonanza wheat farm and ranch for shorthorn cattle. The farm was equipped with a 24-room home and swimming pool, numerous barns and outbuildings, a boarding house and separate residences for farm workers, grain elevators, two large silos that at the time were the largest ever built, a machine shop, an electric generating plant, and a water tower.”

It was during his run on the Northcote farm that Jones would further his education in electronics and go on to earn his engineering license. In an interview with Steven M. Spencer of the Saturday Evening Post, Jones spoke fondly of Hallock, saying that it was a place where a man was “judged more for his character and ability than for the color of his skin.” He left the farm just before it was ultimately sold off but remained in Hallock for the next 18 years.

Midway into World War I, Jones served in France with an all-black Army unit until military superiors realized his innate talents. Before long, he was maintaining communications and electronic equipment, running electric, telephone, and telegraph lines, fixing X-ray machines, and repairing military vehicles. Jones was even promoted to sergeant. After being discharged from the Army in 1919, Jones returned to Hallock, Minnesota, where his inventions started to proliferate. But he failed to patent many of his early innovations, so later inventors received credit. This was true of his condenser microphone, personal radios, and a snowmobile he fashioned from the fuselage of an airplane and mounted on four skis. He attached a motor to power it but the contraption had no brakes, so Jones had to dig his heels into the snow to bring it to a stop. With the use of his “snow machine,” as he called it, Jones drove doctors across the snow-covered fields of Minnesota to make necessary house calls. This also allowed Jones to make ends meet during those harsh conditions.

Jones also built a wireless broadcasting transmitter for a local radio station. But it was while working as a projectionist at the Hallock movie theater that Jones’s innovations brought him into contact with a man who would change his life. In those early days of silent moving pictures, images flickered on-screen. Jones devised a process to lessen this. He also turned silent pictures into “talking” ones by pairing silent movie projectors to talking movie stock. When the industry switched to full sound, theater operators had to buy pricey new equipment to keep pace and make it all work, otherwise picture and sound would be out of sync. The Hallock theater could not afford the upgrade, so Jones took it upon himself to build the necessary components for under $100. The sound quality, as a result, was better than that of the official equipment. With these and other improvements to the theater, Jones caught the attention of the head of a Minneapolis company called Cinema Supplies. That man was Joseph Numero, and in 1930, he offered to hire Jones as an electrical engineer. That ended Jones’s long stay in Hallock.

After moving to Minneapolis, Jones finally began patenting his inventions. The first patent he received was for a movie-ticket-dispensing machine that returned change. That invention survived until the early ’90s. But his legacy was cemented with an invention that revolutionized the food industry. It all started on a Minnesota golf course in the summer of 1938. Joseph Numero was playing against two business associates, one of whom was named Harry Werner, an executive in the trucking industry. Refrigeration historian Bern Nagengast details the exchange in his book Heat and Cold: Mastering the Great Indoors.

Werner learned that he had recently lost a carload of chickens in transit. To properly frame this, in the 1930s, transporting products that required controlled climates was still in an experimental phase, with various methods resulting in abject failure. Early portable cooling units succumbed to road vibration, therefore ice was the go-to option, but it didn’t last long, particularly in the summertime. Being that it was summer, Werner explained that:

“The trip took longer than it was supposed to, and the chickens overheated.”

He then expressed to the third golfer, who was in the air-conditioning industry, that he should invent something to prevent poultry and other foods from spoiling during long road trips. This led to a broader discussion on refrigeration during long-haul transports. Numero half-heartedly offered to build a cooling unit for Werner’s trucks. Werner immediately accepted and had a truck delivered to Cinema Supplies for outfitting. Numero didn’t think a unit could be built for the trucks, and he was ready to tell Werner just that, but Jones took a look at the trailer, made some measurements, and decided to try his hand at it.

In a matter of weeks, Jones completed his shockproof cooling unit, thus the refrigerated semi-truck was born. The invention received a U.S. patent on July 12, 1940, and on the strength of it, Numero sold his company to RCA. Numero and Jones quit the movie theater business altogether and formed a partnership called U.S. Thermo Control Company, of which Jones was chief engineer and vice president. Foods that required controlled climates no longer spoiled en route when transported in trucks outfitted with Jones’s invention. Thermo Control Company (later renamed Thermo King) developed refrigerated trucks that transported food to soldiers during World War II. And in postwar America, the delivery of fresh food to far-flung locations happened year-round. The shipping and grocery industries were completely altered.

Renowned as one of the most prolific inventors that ever lived, Frederick McKinley Jones survived the Jim Crow era, endured poverty, racism, and discrimination, yet achieved tremendous success in his field as an acclaimed genius. The company he co-founded, Thermo King, quickly became a multi-million dollar corporation, which now employs thousands of people as a pioneer and leader in transport refrigeration. But Jones’s many accomplishments and triumphs, together with his towering influence, transcend all of that.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in The Black History Activity Book.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

A brief history of Black History Month, the annual celebration of black achievement, and recognition of the central role black people have played in shaping U.S. culture and history.