The Newark Riots

The Truth About the 1967 Uprising

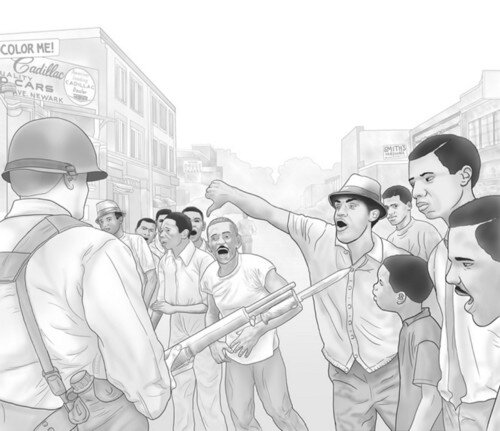

July 17, 1967 file photo adapted from AFP/Getty Images. Depicts black demonstrators facing armed soldiers in Newark during the riots.

Newark, New Jersey used to be a thriving all-white city, from its factory workers, to its department store chains, like Bamberger’s and Hahne’s, which catered to whites. When people of other ethnicities began migrating to the city — particularly blacks — things started to change . . . for the worse. Over time, the city would go from a thriving, white-centric metropolis to a racial powder keg that would explode with tremendous violence toward the close of the 1960s.

This post contains affiliate links. I may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made through links on this page.

The Newark Riots: Origins of a Diverse City

Way back in 1666, English-born colonial leader and militia officer Robert Treat, led a group of Connecticut Puritans south to a land he wanted to be called Milford, New Jersey, after the Connecticut town he had left. But Abraham Pierson, who had led another group of Puritans to the area, opted for New Ark (as in a new ark of the covenant),¹ and so Newark was named. Newark endured raids by British troops during the American Revolutionary War and went from being a township to a city in 1836. That very century, and partway into the next saw Newark grow into an industrial powerhouse as its white population increased.

The Newark Riots: The Impact of Black Migration

Around the year 1900 blacks made up only 3 to 4 percent of Newark’s population,² but by 1910, poor economic conditions and Jim Crow segregation laws in the South forced blacks to migrate to cities in the North, including Newark. This turn of events caused a percentage of the white population to move out of the city. White flight truly ramped up in the 1950s, during the Second Great Migration of blacks from the South. The federal highway department aided in the flight of whites to the suburbs when they constructed highways leading from Newark into new suburban areas of New Jersey. Prior to that time all that existed were pretty much cities and the country. The government made moving affordable for whites through low-cost federal mortgages.

In the midst of white flight, the Interstate Highway System was formed under President Eisenhower and a new highway was planned, which would run through northern New Jersey. The section between Phillipsburg and Newark began construction in the ’60s. It would become route 78, the very highway that destroyed predominantly black communities in Newark’s South Ward for the sake of whites, who needed a way to commute to and from the new suburbs. Many houses were destroyed, forcing blacks, who had once lived comfortably, to find new neighborhoods. Slowly the Jews, the Irish, and the Italians vacated the other Wards, leaving Puerto Rican, Portuguese, and mostly black residents behind.

When the whites left, many businesses dried up, and money stopped flowing into Newark as it once did. This led to high rates of unemployment and severe poverty. Blacks who tried to find jobs and better housing were discriminated against, and so they sank into poverty as well. By 1967, Newark had become a majority-black American city, but one that was ruled by white politicians and policed by white officers. This led to racial profiling, police brutality, neighborhoods being redlined, and blacks being denied access to education and job training, leaving them powerless and entirely disenfranchised as a people. Despite being the majority residents, blacks did not have adequate political representation in Newark, and then came more housing destruction in the name of urban renewal, when thousands of black residents were forcibly displaced from low-income tenement buildings that were demolished in the Central Ward to make room for the University of Medicine and Dentistry.

The Spark that Ignited the Newark Riots

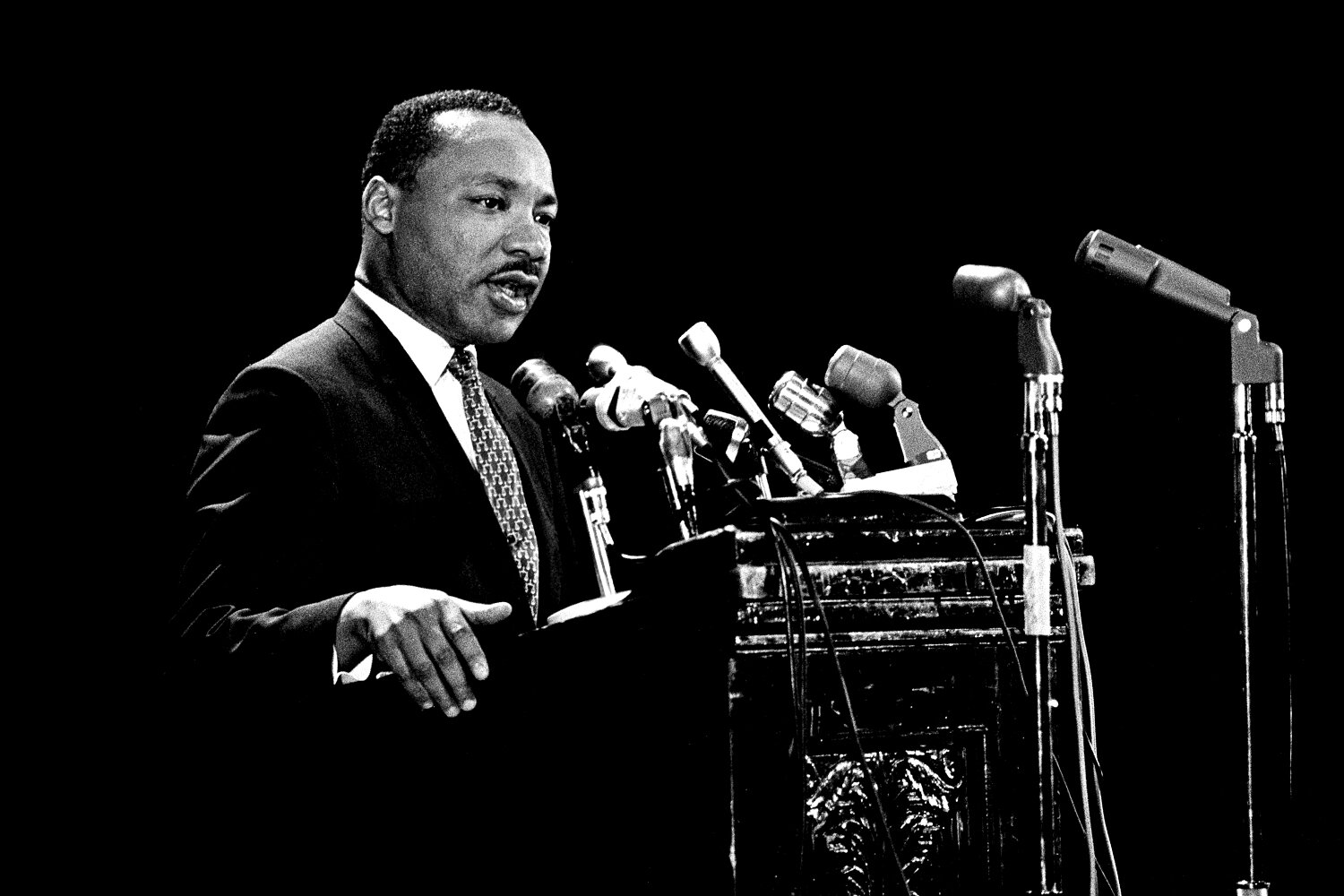

Needless to say, racial tensions were running high in the city of Newark. Three months prior to the infamous uprising that led to riots and looting, Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered a speech at Stanford University predicting the unrest to come. In that speech, titled “The Other America,” King said:

“So these conditions — the persistence of widespread poverty, of slums, and of tragic conditions in schools, and other areas of life — all of these things have brought about a great deal of despair, and a great deal of desperation; a great deal of disappointment and even bitterness in the Negro communities. Today all of our cities confront huge problems. All of our cities are potentially powder kegs as a result of the continued existence of these conditions. Many in moments of anger — many in moments of deep bitterness — engage in riots…. I think America must see that riots do not develop out of thin air. Certain conditions continue to exist in our society which must be condemned as vigorously as we condemn riots.

“But in the final analysis, a riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it that America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice, equality, and humanity. And so in a real sense our nation’s summers of riots are caused by our nation’s winters of delay. And as long as America postpones justice, we stand in the position of having these recurrences of violence and riots over and over again.”

“I think America must see that riots do not develop out of thin air.”

Newark’s summer of violence was sparked on the night of July 12, 1967 and lasted for five agonizing days. It all started with a rumor that was quickly spread throughout Newark. Two white officers arrested and beat a black cab driver named John Smith after he drove past their parked vehicle. Bystanders said this was done without any provocation whatsoever on the part of Smith. The officers were from the notorious 4th Precinct, and black residents thought Smith had been killed inside.

“They started draggin’ me through the streets, and this evidently incensed the people of the community.”

— John Smith

Smith, who was very much alive, had been charged with assaulting the two officers and verbally insulting them. Crowds of black spectators followed Smith as he was dragged through the streets of Central Ward and they waited outside the precinct. Police ordered them to engage in peaceful protests, but the belief that Smith had been killed was enough to incite an uprising. Officers responded with force.

The very thing that Martin Luther King, Jr. had spoken about in his speech three months earlier began to unfold. A long-oppressed community reacted with violence and riots, as they looted neighborhood stores and set buildings ablaze with Molotov cocktails. Before long, police officers were given shotguns and the entire force was placed on emergency duty. They were also told to “fire if necessary.” Prior to 3:00 a.m., the National Guard and state police were called in to deal with the angry crowds.

As the police and military presence increased, the violence escalated. On the evening of July 15, Rebecca Brown, a nurse’s aide and mother of four, was ruthlessly gunned down in her second-floor apartment by state police and National Guardsmen who were randomly opening fire at the upper floors of buildings in response to reports of a sniper being in the area. Fifty-three-year-old grandmother Hattie Gainer was killed in the same apartment building while sitting by her window as she often liked to do. Eloise Spellman, a mother of 11 children, was shot and killed in her 10th-floor apartment for the same reason. The alleged sniper, who was never proven to exist, was reportedly never found either.

When the violence, looting, destruction, and rioting ended, 26 people in total had died or been killed as a result, among them 16 civilians, 8 suspected looters and rioters, one police officer, and one firefighter. Another 727 people were reportedly injured, from civilians to military personnel, and 1,500 others were arrested. The property damage cost the city about $10 million dollars (over $75 million when accounting for inflation). The armed response by the government was strong, with some 7,900 men being deployed in the city.

The Newark Riots: The Legacy of Resistance and Reform

In the aftermath of the riots, Newark steadily declined, as did neighboring communities. Poverty increased and racial discrimination persisted. In the next decade, major industries pulled up stakes and vacated Newark, along with the white middle class. Author Kevin Mumford writes in his book Newark: A History of Race, Rights, and Riots in America:

“Deindustrialization had accelerated sharply, and by the mid-1970s both Mutual Insurance and Prudential Insurance cut employees . . . while several major manufacturers . . . closed their operations. . . . By the 1970s, black youth unemployment increased to an annual average of 45–50 percent, compared to the already high average unemployment rate of 12 to 14 percent for the city. . . . [M]any economic analysts attributed urban decline to the tax structure. For reasons that few could explain, Newark assessed the highest property tax in the nation. . . .”

On July 7, 2017, the Washington Post ran an Associated Press article that stated:

“The 1967 riots prompted President Lyndon Johnson to launch an inquiry into the cause of the racial disorders. Among the findings of the Kerner Commission were that the country ‘is moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.’ The report identified police practices as among the primary factors that led to the unrest in black communities. ‘The abrasive relationship between the police and the minority communities has been a major — and explosive — source of grievance, tension and disorder,’ the report read.”

This led to sweeping changes in law enforcement training across the nation, and, “there are now greater systems of accountability for police officers,” the article also stated. In this, and other ways, Newark experienced a 1967 uprising that changed America. Yet, police brutality still persists, though not to the degree of 1960s Newark. But unless society ceases to marginalize and alienate blacks and other minorities today, the events of that long, hot summer in Newark will stand as a blueprint for what will continue to take place in urban cities of America and countries around the world.

You may also be interested in:

This article appears in The Black History Activity Book.

Available from Amazon.com, BN.com, and other retailers.

More than 150 cities witnessed a wave of violent protests during the sweltering summer months of 1967. This evolved into violent riots that highlighted the dark underbelly that is America’s racial disparity.